How do we forge meaningful conversations with the people around us? That is the question we asked ourselves this past semester in Designing Civic Conversations, an elective taught by Design PHD Michael Arnold Mages. Intimate and discussion-centered, the class of seven was made up of public policy and design grads eager to learn how community outreach and engagement can impact local policy.

Our class was given a specific focus: homelessness in the Pittsburgh region. We were tasked with designing a public event that would engage community members and stakeholders around the issue. Early on in class discussions, we asked: As non-experts, how can we change the public’s perception of people experiencing homelessness? Can we spark conversations outside our event and catalyze citizens to take action? Through research, planning and the creative process, we brought our ideas to life.

Challenge

Homelessness is any city is a complex issue. You have people with powerful stories living on the street, nonprofits and government organizations offering services with limited budgets, city officials making housing policies and dozens of other influencing factors shaping the wicked web. In order to engage our community around homelessness, we found it essential to generate empathy for people living without shelter, through both visual and physical storytelling. Designed as the first event in a series, we sought to share stories from the homeless and encourage people to reframe their biases. To do this, we organized a “Humans of New York” style micro-exhibit and journeying card game called Carrying Homelessness.

Research

We started the semester by creating stakeholder maps that helped us understand the actors, effects and needs of people experiencing homelessness. Through weekly readings, we also learned the value of placemaking, the challenge of addressing wicked problems and communicating effectively. Design theorists, Rittel and Webber explain that the real wicked problem in society is defining the problem itself. For example, most of us identify problems and muster solutions that aligns with our worldview and mental models. It’s not that this is wrong, it’s that there are many possible problems and solutions in a complex society. With this in mind, we made it a point to connect with experienced stakeholders, including Pittsburgh city officials, housing service providers, grassroots organizers and individuals experiencing homelessness in the Pittsburgh community.

Design & Testing

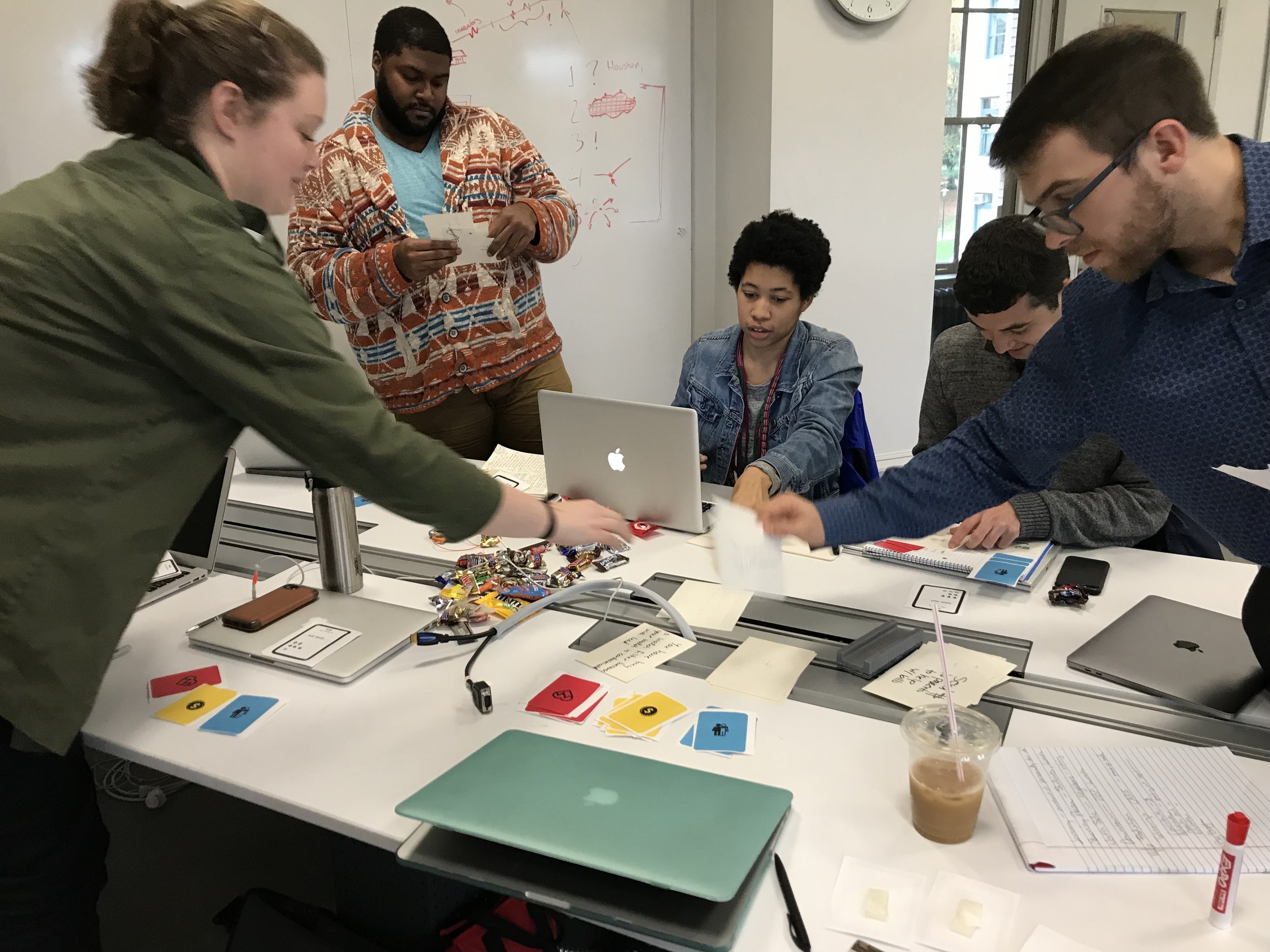

After conducting research and developing event proposals, we integrated the best ideas to create an interactive event: Carrying Homelessness. The event entailed a journeying card game and micro-exhibit that targeted college students. The goal was to break the stigma around people experiencing homelessness and generate more empathy by sharing stories. We spent several class periods testing the journeying card game with students and teachers.

I led the design of the card game. It was developed to be an interactive activity simulating the homelessness experience in Pittsburgh. Through user-testing and input from my class, I determined that attendees would be given playing cards that guide them through the exhibit and unhinge a set of life choices determining their level of housing insecurity. The activity would demonstrate how health, money, and personal relationships combine with social inequality to shape the journey of homelessness.

In addition to the card game, we spoke with people in the homelessness community to learn about the things they carry with them when living on the streets or in a shelter. With these powerful vignettes, we developed posters to share their stories to the Pittsburgh community.

Carrying Homelessness: The Event

We held the event in Schenley Plaza, a public space often used by people in the homeless community. It was a cold day, but we had hot coffee for passerbyers and large posters visible to the sidewalk. The posters brought in students walking to and from class, interested in a quick look at the images and narratives told by people experiencing homelessness in Pittsburgh. Families, professors and leisurely students were also eager to test the journeying game and provided feedback about their experience. As designers, we are taught that a project is never finished, so the event was a valuable way to collect feedback on the experience. Here are a few things we heard:

-Empathy was the clear theme. People said it was a good idea and a fun game that made them think about their own relationships and health challenges.

-Excellent way to practice empathy in a really short period of time

-People wanted more conversation about their cards, more reflection points

Carrying Homelessness was a success. The event attracted more than two dozen University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon students and staff, as well as community members. As a class, we learned how to plan and facilitate a public event that used visual and experiential storytelling to generate conversations among community members. By carrying out a series of events with local stakeholders, these types of one-on-one conversations can generate buzz, catching the attention of city and county officials. Although we had a limited amount of time to dedicate to the project, we hope people continue discussing their experience to friends and use empathy to bridge communities across Pittsburgh.